Walk through any architecture school today, and you’ll notice something striking: the near-total absence of classical design in the curriculum. Corinthian columns, pediments, entablatures—these are treated more as relics of the past than as living elements of architectural language. Instead, students are trained to embrace modernism, minimalism, and the cutting edge. But why? How did classical architecture, which shaped cities for centuries, become almost taboo in architectural education?

1. The Legacy of Modernism: A Clean Break from the Past

The early 20th century was a turning point. With the rise of industrialization, architects like Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, and Mies van der Rohe sought to break free from historical styles. They believed architecture should reflect its own time, embracing new materials—steel, concrete, glass—rather than reinterpreting the past. The Bauhaus movement, which emphasized functionalism and simplicity, took hold in schools and never let go.

By mid-century, modernism had become the dominant architectural ideology, and classical architecture was increasingly dismissed as outdated, even regressive. Architecture schools, eager to align with progress, stopped teaching the classical orders, composition, and proportion, shifting focus toward abstraction, form-making, and technological innovation.

2. The Influence of Ideology and Academia

Architecture is more than just buildings—it’s a reflection of cultural values. In the mid-20th century, classical architecture became associated with aristocracy, conservatism, and historical power structures, while modernism was seen as forward-thinking and egalitarian. Many schools took an almost philosophical stance against classicism, framing it as an obsolete, decorative, and even elitist approach to design.

Postmodernism briefly challenged this orthodoxy in the late 20th century, bringing back historical references, but it was often done with irony rather than reverence. By the 21st century, academia had returned to a largely modernist and postmodernist approach, reinforcing the idea that classical architecture was a historical curiosity rather than a viable design language.

3. The Focus on Innovation Over Tradition

Today’s architecture schools emphasize innovation—pushing boundaries with parametric design, sustainability, and digital fabrication. The idea of looking backward to classical principles doesn’t fit neatly into this framework. Students are encouraged to experiment with unconventional forms rather than refine traditional proportions. The classical method of learning through imitation—once the standard in art and architecture—has been replaced with a focus on conceptual thinking and abstract problem-solving.

4. The Misconception That Classical Means Copying

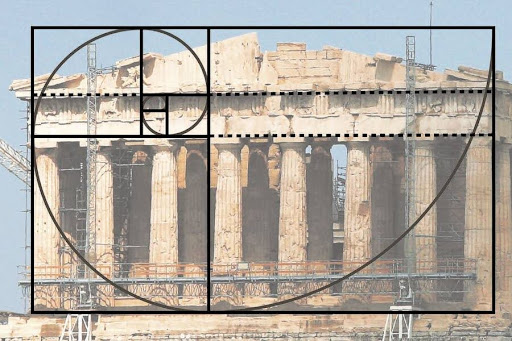

One of the biggest misunderstandings is that classical architecture means rigidly copying the past. In reality, classical design is a system of principles—balance, proportion, harmony—that can be adapted to new materials and modern needs. However, since most architecture students are never exposed to classical training, they often see it as nothing more than historical replication rather than a flexible, evolving design language.

5. The Revival: A Growing Pushback

Despite its exclusion from most architecture programs, classical architecture isn’t dead. Organizations like the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art (ICAA) and movements like New Urbanism are pushing back, advocating for the teaching of traditional design principles. Some architecture schools, particularly in Europe, are slowly reintroducing classical studies, recognizing that history offers valuable lessons for designing livable, beautiful spaces.

Conclusion: A Case for Balance

Modern architecture schools have largely abandoned classical training, favoring innovation and theoretical exploration over tradition. While progress is necessary, the erasure of classical education leaves students without a full understanding of architectural history and its enduring principles. A balanced curriculum—one that includes both the classical and the contemporary—would better prepare architects to create buildings that are not only innovative but also timeless, functional, and human-centered.

Perhaps the future of architecture isn’t about rejecting the past or clinging to it—but about understanding it deeply enough to evolve it.